General information

Although the character of nineteenth-century historiography was more or less defined along the lines of historicism, positivism and the rise of national histories, this was not the case in the twentieth century. In the first part of the century, historians (with a few distinct exceptions) followed the nineteenth-century paradigms. Yet, in the second half of the century, the disciplinary gates opened, boundaries and borders were reconsidered and certainties questioned. A flow of successive trends and turns in methods, theories and ways of approaching, researching, practicing, narrating, writing but also filming, staging and performing history emerged. A new landscape was formed. Ever since, we have changed, or at least we have reconsidered, our terminologies, concepts and perspectives. We have discussed memory, public history, history wars, historical cultures, and the traumas of the past. We have been exploring disciplinary transformations and changing questions and themes. The past seems to have escaped from the mausoleum where nineteenth-century historiography had mummified it, to acquire a new life, to become a ghost that disturbed, annoyed, troubled but also amused and entertained contemporary societies. In this context, it is difficult to conceptualize twentieth-century historiography as a coherent subject of study. Even more so, if we take into account the spread of historiography, history and memory wars around the globe. Historiography has been transplanted everywhere through colonialism and/or anti-colonialism. There is an abundant literature on the various historical trends, on the passages of one turn to the next, on history wars, on memory and public history, on the forms that historical experience and historical consciousness have acquired in the course of the twentieth century. Historical theory has developed into a burgeoning field in recent decades. But little attempt has been made to produce a comprehensive study which would connect the rivers flowing within academia with those running outside it. Hardly any works exist that relate the various turns in historiography to living experiences. History is still treated as an abstract idea, another scholarly field or a literary genre. If we apply to history the distinction made by Ferdinand de Saussure between langue and parole,we could sayhistory is still studied as a langue and rarely as a parole. What is missing most from studies on the twentieth-century’s preoccupations with history is an exploration of the inner and deeper connection and interrelation between the various experiences of the century and the various approaches to history. The twentieth century has been described as ‘the age of extremes’, as the century of catastrophic wars and genocides. It is also the age of feminism, decolonization and techno-scientific evolutions. But how are these experiences linked with historical schools, trends, methods and practices? How have they contributed to our understanding of the past? How can we relate history and historiography in the twentieth century? In what ways has twentieth-century historical experience determined the study of the past? What do disciplinary transformations in the fields of feminist/women’s/gender history, written/oral/audiovisual history, public history, and comparative/transnational history, for example, owe to changing political, cultural and social perspectives and views? Are ‘disciplinary turns’ linked to ‘epochal turns’ and, if so, how are they linked in particular contexts? How have common turns and particular/national methodologies intermingled? How ‘French’ was the French histoire totale, how ‘Italian’ was micro history, and what does new historicism owe to the English intellectual tradition? What about forgotten or abandoned historical trends and traditions? The ways in which they are connected with historical experience and ways of remembrance is one of the key questions of this conference. And are key concepts like truth, impartiality and objectivity still valuable for historians, and how have these concepts changed from one era to the next and from one cultural milieu to the other? Transforming subjectivities is another focus of the conference. How have historians conceptualized epochal turns or specific historical facts, how have they experienced them, how have they affected their changing perspectives and intellectual processes? This conference will explore these connections between ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ processes and realities, between ‘internal’ and ‘external’ influences and between ‘the academic’ and ‘the non-academic’ with regard to historical thinking and feeling, in an attempt to trace the links between the different forms of the historical, the multiplicity of historical subjectivities (including the subjectivities of historians themselves) and the various collective experiences of the twentieth century.

Programme

Venue and how to get there

Hotels and tourist info

The conference will be held at the Central Buildings of the University of Athens (Panepistimiou 30).

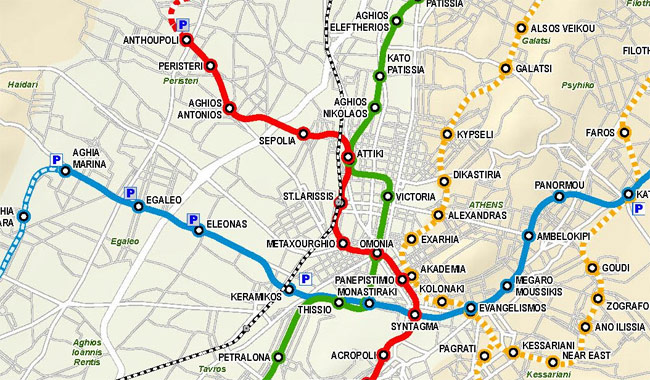

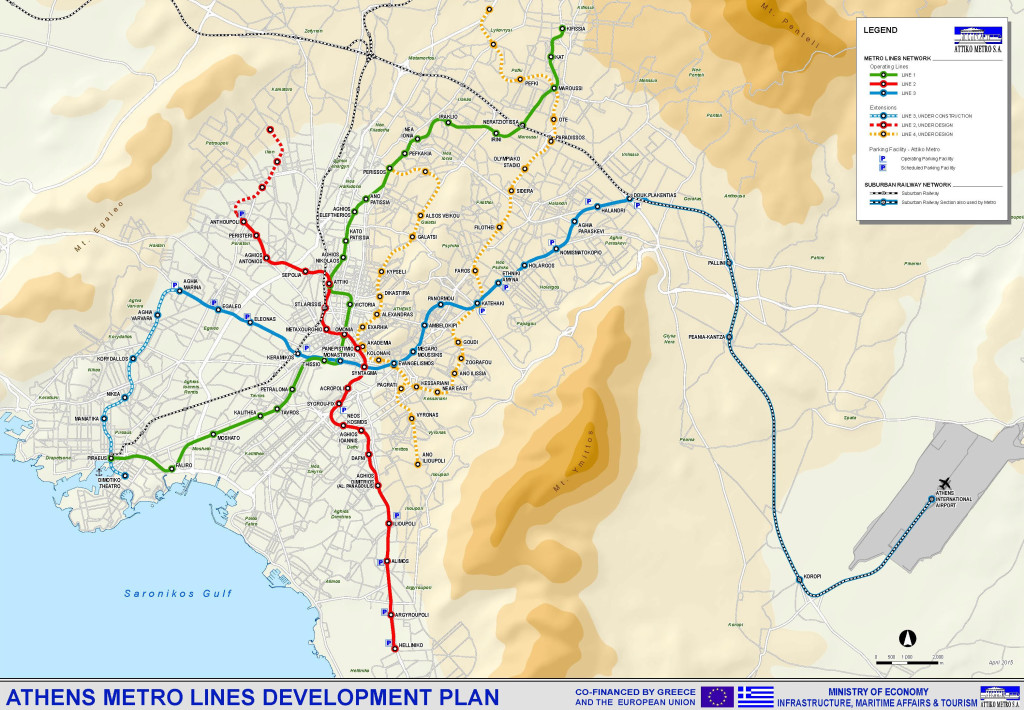

That is at the city-center, and the Metro-stop “Panepistimio” (red line) stops exactly outside the conference venue. Getting to the Conference Venue:

- From Syntagma square: A 10’ minutes walking distance down Panepistimiou Str., or Red Metro Line towards Anthoupoli, Panepistimiou stop (1 stop)

- From Omonia Square: A 15 minutes walking distance up Panepistimiou Str., or Red Metro Line towards Elliniko, Panepistimiou stop (1 stop).